Julia Elyachar

Julia Elyachar is an author, anthropologist, and political economist.

Elyachar is trained in anthropology, economics, history of political and economic thought, political economy, social theory, Middle Eastern Studies, and Arabic language. She is associate professor of anthropology at Princeton University, and associate professor at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. She is also a Faculty Researcher with the Dignity and Debt network and serves on the Executive Boards of the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, and the Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies.

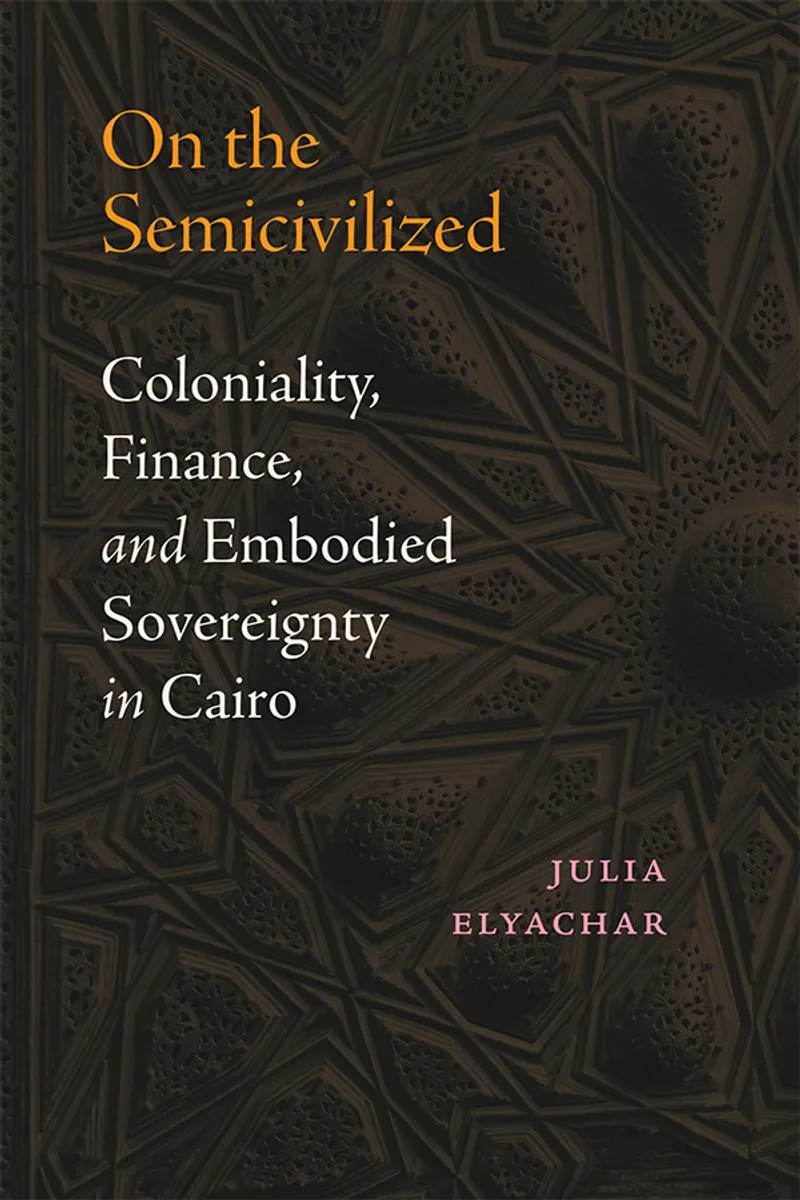

New book: On the Semicivilized

Julia Elyachar

Julia Elyachar is an author, anthropologist, and political economist.

Elyachar is trained in anthropology, economics, history of political and economic thought, political economy, social theory, Middle Eastern Studies, and Arabic language. She is associate professor of anthropology at Princeton University, and associate professor at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. She is also a Faculty Researcher with the Dignity and Debt network and serves on the Executive Boards of the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, and the Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies.

New book: On the Semicivilized

On the Semicivilized

Coloniality, Finance, and Embodied Sovereignty in Cairo

On the Semicivilized

Coloniality, Finance, and Embodied Sovereignty in Cairo

On the Semicivilized is a sweeping analysis of the coloniality that shaped—and blocked—sovereign futures for those dubbed barbarian and semicivilized in the former Ottoman Empire.

Drawing on thirty years of ethnographic research in Cairo, family archives from Palestine and Egypt, and research on Ottoman debt and finance, Elyachar theorizes a global condition of the “semicivilized” marked by nonsovereign futures, crippling debts, and the constant specter of violence exercised by those who call themselves civilized, inviting us to rethink catastrophe and potentiality in Cairo and the world today.

Recent articles and chapters

About Professor Elyachar

Julia Elyachar is associate professor of anthropology at the Princeton University Department of Anthropology and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. She is the author of the books On the Semicivilized: Coloniality, Finance, and Embodied Sovereignty in Cairo and Markets of Dispossession: NGOs, Economic Development, and the State in Cairo. Her work draws on fine-grained ethnography and regional expertise in the Middle East, Levant, and the Maghreb to open up areas for theoretical inquiry and conceptional innovation in anthropology and the social sciences more broadly.

About Professor Elyachar

Julia Elyachar is associate professor of anthropology at the Princeton University Department of Anthropology and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. She is the author of the books On the Semicivilized: Coloniality, Finance, and Embodied Sovereignty in Cairo and Markets of Dispossession: NGOs, Economic Development, and the State in Cairo. Her work draws on fine-grained ethnography and regional expertise in the Middle East, Levant, and the Maghreb to open up areas for theoretical inquiry and conceptional innovation in anthropology and the social sciences more broadly.

Events

Feb

12

2026

SOAS Public Talk about On the Semicivilized

University of London - SOAS

Public TalkLocation: University of LondonLinkIn the series: "Histories of Capitalism and Race in the Middle East and Beyond," School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

Mar

3

2026

Book Talk at Columbia University, Julia Elyachar: "On the Semicivilized"

Department of Anthropology and MIddle East Institute, Columbia University

Book talkLocation: Columbia UniversityBook talk by Julia Elyachar about her book On the Semicivilized: Coloniality, Finance, and Embodied Infrastructure in Cairo.